THE POWER OF OWNERSHIP, PART 1: THE BEN & JERRY’S TRAP

“Getting [purchased] by a huge multinational works against what I believe is needed to create a more equitable society.”

That quote comes from a recent New York Times interview with Ben Cohen, co-founder and namesake of Ben & Jerry’s. He is referring to his company’s sale, in 2000, to the conglomerate food giant Unilever.

Given his philosophical position that selling to Unilever was antithetical to building “a more equitable society,” why then did Cohen, and co-founder Jerry Greenfield, decide to sell their company?

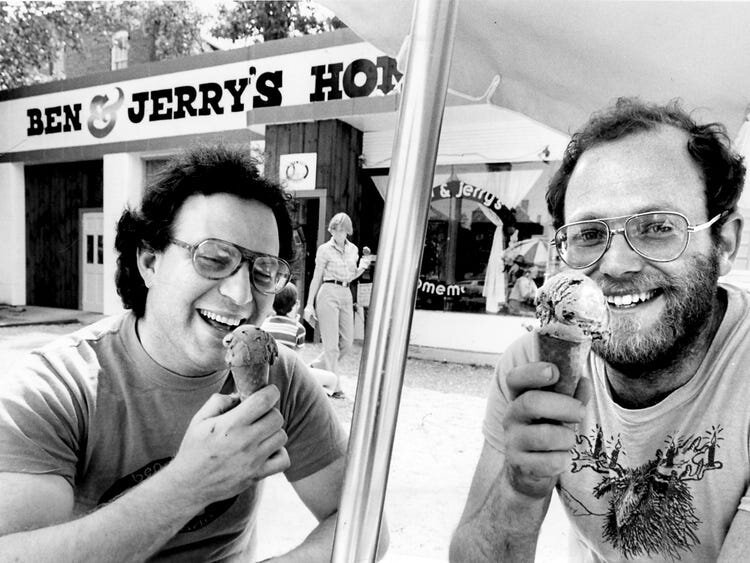

The obvious answer is that they, and their shareholders, wanted to make a lot of money. After all, Cohen and Greenfield started the company in 1978, and by the time Unilever came knocking they had been working hard for 22 years. Nobody could blame them for wanting to sell their stake and retire in comfort (they walked away with a combined 50M dollars).

But that simple story doesn’t paint the full picture.

By the year 2000, Ben and Jerry were not the only owners of their ice cream kingdom. To raise capital, the company had previously done a direct public offering in Vermont. And with that offering came outside shareholders and a board of directors. While the two founders maintained a large chunk of ownership and control, it was no longer solely “their company.”

So when Unilever and Dreyer’s both came to the table with offers to buy the company at a healthy premium, Ben and Jerry’s board of directors, on behalf of the shareholders, felt obliged to listen, and ultimately to sell to the highest bidder.

It didn’t have to end that way. In fact, it almost didn’t end that way.

The craziest part of the Ben & Jerry’s exit story that most people don’t know is that in a final effort to stay independent, an insider group of impact investors led by Cohen and facilitated by the investment bank Meadowbrook Lane put together a strong competing offer to purchase the company and take it private (surprisingly, this group actually included Unilever in a minority financing position).

As The New York Times reported at the time: “The Meadowbrook proposal would take Ben & Jerry's private, replacing the current board with one composed of ‘leaders of the socially responsible investment community as well as from the food and financial industries.’ A separate board of advisers would focus on making Ben & Jerry's ‘the most active socially responsible company’ in the country. Meadowbrook says it would continue financing the Ben & Jerry's foundation and set up a venture capital fund to foster other companies with similar values.”

Despite the promise and seriousness of the insider bid for independence, Unilever ultimately won the auction outright and purchased the company for $43.60 per share, outbidding Cohen and Meadowbrook’s offer of $38 per share.

In a 2010 NPR radio segment, Cohen reiterated that the sale to Unilever was not their first choice: “the laws required the board of directors of Ben & Jerry’s to take an offer, to sell the company despite the fact that they did not want to sell the company.”

Whether or not Ben & Jerry’s directors truly had a legal obligation to maximize profit and sell to Unilever is questionable. In terms of how a company chooses to operate, the profit maximization precedent is based on the 1919 Supreme Court opinion in Dodge v. Ford, which according to Lynn Stout, is now treated as “a dead letter” by the courts. In actuality, Stout argues, corporate boards have the legal right to consider a much broader set of criteria beyond just profit in their decision making. However, this precedent may only extend to the operational decisions of a company, and may not be applicable when considering a potential sale.

In situations involving the inevitable sale or breakup of a business, there are other legal precedents, perhaps most notably Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, that may obligate a Board of Directors to maximize the sale price of a company for the benefit of stockholders. In such cases, which may very well have included Ben & Jerry’s, there is clearly a direct conflict between a company’s purpose and the fiduciary obligation to give shareholders the most lucrative possible exit.

Regardless of what a court might have ruled if given the opportunity in this case, the corporate fiduciary obligation to maximize profit certainly represents the conventional wisdom in the United States. Further, within traditional corporate structures, regardless of the law, there is immense pressure to maximize shareholder value (not to mention personal wealth for the share-owning board members and company managers).

Legal debates aside, if we take Cohen at his word that they did not want to sell, but were essentially forced to sell, the obvious next question becomes, how could this have been prevented?

One compelling answer to that question can be found in Ben and Jerry’s corporate structure.

What if, instead of a conventional structure that “required the board of directors to ... sell the company despite the fact they did not want to,” the company had had a structure that legally protected it from this fate?

In this alternative reality...

All of the voting shares of the company are held in a Perpetual Purpose Trust responsible for ensuring that the company maximizes purpose.

The Board of Directors and the company managers are aligned and legally supported in their premise that profits are a means to an end, and not an end in themselves.

The shareholders of Ben and Jerry’s are still entitled to share in the profits of the company, but they don’t have a vote to sell the company, change its purpose, or replace its Board.

The company is under no obligation to entertain unsolicited bids.

In this alternative reality, Cohen’s quote might have read like this: “The laws required the board and the trustees to maintain Ben & Jerry’s independence and to advance the company’s social and environmental goals, and therefore we were unable to accept any offer that wasn’t explicitly designed to further that cause.”

Guess what? That reality is not a pipe dream. It is real and it has a name: steward ownership.

The philosophy of steward ownership is based on the premise that corporations have a role beyond generating profits. That at their core, companies can and should have a reason for existing that is rooted in a purpose greater than “making money for shareholders.”

Steward-owned companies are designed for permanent independence - they are not a commodity that can be bought and sold. In a steward-owned company, control is maintained by those who have an interest in this purpose. In concrete terms, this means that voting shares can only be held by designated “stewards” who are bound to advance the company’s purpose. Companies can still raise money or create liquidity by issuing other shares with economic rights, but they do not have the right to sell the company or take control.

Finally, many steward-owned companies are designed to serve a broader range of stakeholders beyond just shareholders. This commitment is explicit and built into the ownership and governance of the company, ensuring that it lasts no matter who the executives or board members may be in any given year.

This is not just theory. The legal infrastructure to support steward ownership already exists in the form of purpose trusts, multi-stakeholder co-ops, veto shares, and foundation ownership, to name a few.

If Ben & Jerry’s had been steward-owned, and the sale had never happened, what would have been different? We will never know for sure, but depending on the company’s purpose statement and structure, it might have meant more profit sharing and wealth-building for employees, more sustainably sourced ingredients, even humanely treated dairy cows, and better prices for farmers. Further, it might have inspired hundreds of fledgling companies to model themselves after Ben & Jerry’s and pursue their own steward ownership journey.

The primary obstacle to greater adoption of steward ownership is not technical nor legal (the tools and frameworks exist), but awareness. Most founders and business owners simply are not aware that alternatives even exist.

In Part 2 of this series, coming next month, we will highlight four large, privately-held companies that we think should consider a steward ownership conversion now to protect themselves against “The Ben & Jerry’s Trap.”